- Home

- Tim Buckley

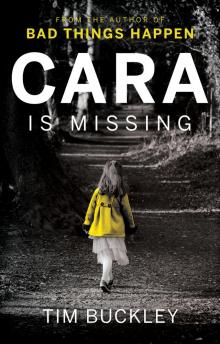

Cara is Missing

Cara is Missing Read online

Cara

is

Missing

Tim Buckley

Copyright © 2019 Tim Buckley

Cover Photo by Mark Buckley

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 9781789019827

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador® is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

For Amanda.

For everything.

Forever.

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

1

I’m about to knock one more time on the front door when I hear the sound of footsteps on the stairs inside and it opens just the length of the chain. She’s hiding herself behind the door and, when she peeks out through the crack, her hair is dishevelled and her eyes are still half-closed, not yet quite awake.

“Oh, Wilde,” she says, as though I’m the last person she expected to see at her door even though I spoke to her only yesterday, “it’s you? You’re early.”

I look at my watch and shake my head.

“No,” I say, “I’m not. It’s just gone nine.”

Now she’s flustered. Emily isn’t comfortable anymore with the unexpected and she gets rattled if she feels somehow outmanoeuvred. Especially if it’s me, and especially now. I can see her scrabbling through her sleep-muddled head for a way out of the awkwardness and one that isn’t going to descend into a fight. I’m tempted to let her squirm, I want to want to enjoy her discomfort. But I don’t, because I know I won’t.

“Look,” I say, “I’ll pop down to The Pantry and get a couple of coffees. I’ll be back in fifteen minutes, yeah?”

She nods her head and I turn back down the path to the little courtyard of packed bright red earth where I’ve parked the car.

“Thanks, Wilde,” she calls out to my back.

It’s still early on a Saturday but already the road into town has been awake for hours. Cape Rijker Avenue is lined on either side by sensible detached houses with shiny cars and neat gardens where lawnmowers and hedge-cutters hum and buzz respectfully. In the early days, we would walk into town past these same houses and, in the way of a small town, we got to know some of the people who lived along the way and caught little glimpses into their lives. The Gregsons have brought the boat up from the marina after a lazy summer of sailing up and down the coast. They’ll soon be washing it down and cleaning it up before they wrap it in its winter tarpaulin. Old Mr Buechler will give his vintage Alfa Romeo convertible a final polish before it goes back into the garage until spring. He’s as blind as a field mouse these days, so he never drives it anymore – just polishes it and sits in it, listening to the radio. Maybe he’s lost in thoughts of days gone by when he and Mrs Buechler would roar down the Ocean Road, her hair wrapped in an Audrey Hepburn scarf, sunglasses covering her face, head tossed back and bright red lips laughing at something he’s said. I don’t know if they ever took the Alfa along the clifftops, but I like to think that they did.

I pass the new school and pull into town along the seafront, parking the car outside the post office and stopping for a moment to look past the bus stop on the far side of the street to the beach huts and past them to the ocean. The sky is that rich West Australian mauvy-blue and the sun is getting bright. The huge white gulls that used to terrorise me when we first moved here are hovering on the thermals, watching me with beady, bastard eyes, waiting. The breeze is freshening too, chasing the clouds and whipping up little whitecaps that upset the surface of the water like careless icing on a birthday cake. A couple of kitesurfers zip across the bay, wetsuited against the morning chill. The summer is on the wane and ready to make way for autumn. Yet another autumn.

The Pantry is quiet, it’s still early. Bobby isn’t behind the counter and I’m glad, I’m not ready for that conversation. There’s a young girl working there that I haven’t seen before, one of the steady stream of high-school kids who make their pocket money brewing coffee and wiping tables and tapping on their phones while they wait for another customer. I’m sure I know her or her parents, but they all look the same to me now. She smiles at me nervously as I walk up to the counter; maybe it’s her first day. The apron that she’s inherited from the last kid is faded with washing; it’s a little bit too big for her and it doesn’t sit quite right.

“Good morning,” she says, still smiling but without conviction, “how are you today?”

“Good thanks. Can I get a long black and a flat white – extra shot, skim milk and half a teaspoon of cinnamon on top, please? To go.”

“Sure.”

She sets about the coffees and I look around the café, all waxed wood and chunky furniture and brightly coloured condiment jars. This is Bobby’s pride and joy, her dream come true, and her sweat and tears are dried into every table and chair. Even her blood – like the evening she stabbed herself with an old screwdriver trying to put a broken stool back together after a schoolkid had leaned back on it one time too many and crashed splintering to the floor. I took her to the emergency room that night and waited while they stitche

d her up.

“I bloody told him, must’ve told him a hundred times,” she complained all the way home, “don’t lean back so far – you’re too big and it’ll break. Bloody kids…!”

The girl behind the counter is battling with the coffee machine, the milk-steamer has stopped working and she’s twisting it one way and then the other but all to no avail. Suddenly, it belches back to life and blows a gust of steam into the milk jug, sending frothed milk to the clouds and all over the machine and the floor.

“Oh, shit!” she says, then blushes at the word. “Sorry…”

She’s frantically mopping and wiping and cleaning the milk from every surface, throwing wads of blue paper towel into the bin.

“I’m really sorry about that,” she says again, “I’ll get your drinks right now.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I say, “there’s no rush. Take your time.”

She takes a deep breath and turns back to the machine. I imagine her talking to it under her breath, begging it to be nice, just to be nice this one time. I know how she feels. I feel for her.

***

I don’t remember the first time I met Bobby, it feels somehow like I knew her before we got here and carried on from where we’d left off in some other life. Our paths crossed when her son, Karl, answered an ad that Emily put up in the local shop looking for some help with the vines. It was just dogsbody work, really, but Karl was a nice lad, worked hard and we trusted him around the place. Bobby would come to pick him up or drop him off when his bicycle was knackered or had been nicked. She became a mate, so much so that, when I talked about stuff we’d done, people who didn’t know her would assume that she was a bloke until a pronoun pointed out the mistake. We ran and biked a bit and even took part in the odd race at the weekends during the summer. We’d trail in long after the winners had collected their medals and gone home but those sweat-soaked hours on the road were important times that took me out of myself and freed my head from the shackles of long hours spent staring at a screen or fretting about the lighthouse. Or about Cara.

Bobby and Emily didn’t really get along. It’s not that “they didn’t get along”, rather that they didn’t “get along”. They didn’t argue or fight nor was there any bitchiness or jealousy – Emily wasn’t at all worried about my relationship with Bobby and there was no reason she should have been. Like I said, Bobby was a mate and I’ve never really thought of her as even having a gender. No, they didn’t get along simply because they were such different people, with nothing in common. And I mean nothing. It might take time, but even polar opposites that I’ve known have managed to find something that they shared, no matter how obscure or immaterial. They might only like the same herbal tea or hate the same Bronski Beat song, but that at least creates a connection that allows them to be together or to be in the same group. But Emily and Bobby share nothing. Emily might not have spent much of her life living in France but she is still French and that blood will run through her wherever she ends up living. She loves clothes and shoes, Bobby is happy in yesterday’s jeans and a T-shirt. Emily loves to cook and to experiment with new wines, Bobby loves a delivery pizza and a cold beer. Emily had long ago written the story of her life and she was always chasing its happy ending, Bobby just wants to be happy in the now. It’s not like there was any acrimony between them, they just had nothing to say to each other. They found each other’s company uncomfortable and I found it uncomfortable to be with them both.

Karl came out of a marriage that was destined for disaster from the moment they left the altar. Mitch played footie for a third-rate team in a third-rate regional competition, but he nurtured dreams of greatness and the big time. To be fair to him – and that’s sometimes difficult – he had his share of bad luck along the way. A scout from the big leagues discovered him as a teenager and he was headed for the Holden Cup with Brisbane until a cruciate ligament injury scuppered the deal. He was left to languish and to watch from the sidelines as other kids, kids with a lot less natural ability than him, lived out his dream. Eventually he coped only because he was drunk most of the time. He was hopelessly unprepared for life as a father and avoided Karl as much as he could. Karl, of course, idolised him and copied everything he did and said. Inevitably, Bobby threw Mitch out and he wound up wandering from club to club up and down the country on short-term contracts searching for glory.

That was when Bobby opened The Pantry, selling coffee and her own home-made cakes and sandwiches and finding, at last, something she was really good at and something she actually loved doing. Like I said, she was different to Emily in that she was happy to bake and cook and clean the coffee machine every day and to do it again tomorrow and the day after. She didn’t need the promise of better, perhaps because she had known so much worse. Bobby might have been my best mate, and there’s no doubt she got me through a lot of the really bad times. But I’m glad all the same that she’s not here. Not today.

***

When I knock on the door again, she opens it immediately as though she’s been standing on the other side, waiting. Maybe she was.

“Thank you,” she says, reaching out to take her coffee. She looks at it like it’s an old friend. “I really need this.”

She’s obviously showered and thrown on her “slopping around for the weekend” clothes, but she’s still the kind of beautiful that looks effortless, careless almost. Her tanned skin, bronzed from days working on the vines under a hot sun, glows under a white T-shirt. Her jet-black hair, pulled back from her face and tied up in a ponytail, shines in the sunlight. Her long, slender legs are bare under cut-off shorts and her toes are tipped with bright nail polish. There’s not a thing out of place but, all the same, she looks tired and if it was someone else I might make a joke about a late night and too much red wine. I might roll my eyes in mock admonishment. But the last thing I want to hear is that she was out having a good time with her friends. Or with a new friend. A new friend who was still here when I arrived this morning? I especially don’t want to hear that. I don’t want her to have somebody new but, really, I know she won’t, not yet and not like this. That’s not Emily’s way. I want her to be OK… but really, I don’t. I want her to still need me. Fuck it.

“Come in,” she says, leading the way, inviting me into my own home.

We did so much work on this place, it’s unrecognisable from the stuffy, run-down old wreck that we bought a million years ago. Five years ago. The first day we went to see it, we must have spent two hours driving round in circles on potholed, rutted roads. The farm was on a by-road off a by-road that led to nowhere and we were on the cusp of giving up when we finally pulled up in the dusty front yard, overgrown with tough, hard-stemmed weeds. We could hear the shutters clatter in the wind against the wooden frame of the house where their clips had rusted away and broken, like angry shots across the bows of interlopers. Pale blue paint flaked and peeled from the clapboard and loose corrugated iron panels flapped on the outbuildings like an old man playing a wobbleboard. Inside, the air was heavy with the stale reek of neglect. The old woman had lived there alone for twenty years, since her husband died. Before that, they’d lived there for another ten or fifteen. After he died, she’d either been unable to manage the upkeep or she simply didn’t care anymore. Either way, the years of grime were caked into the walls and ground into the floors. I whispered to Emily that the place smelled like maybe she’d kept the old man and packed him in the loft or in the hall closet.

“Sshh!” she scolded, elbowing me in the ribs with a glower although I could see she wanted to grin.

“What was that, my dear?” The estate agent was a fifty-something woman trying to be twenty-something with bouffant hair, fake tan and a plunging neckline. She’d been showing us houses in the area for months. She was getting tired of our ever-changing wish list and we were tiring of her ever-more-transparent lies.

“Nothing, Estelle,” Emily said and flashed her most disarming

smile. “Wilde was just saying how useful the storage space would be. You’d be amazed what you’d get into that hall closet, I’d say?”

2

The old truck chuntered into the yard, creaked to a stop and belched a cloud of oily smoke as the engine shuddered and went quiet. Emily looked up from the viticulture book she was studying and then jumped up from the kitchen table.

“They’re here, Wilde,” she squealed, “the sheep are here!”

She ran outside and, taking him slightly aback, hugged the grizzled old driver as he stepped down from the cab.

“And g’day to you too, love,” he said, tipping his hat with a broad, yellow-toothed grin. “So is it me boyish good looks or is it just me truck you’re after?!”

“It’s not you, I’m afraid, it’s these little ones! I’m so glad to see these little ones!”

He shrugged in mock offence.

“Story of my life, love!” he said and handed her an old clipboard from which a chewed plastic biro swung on a piece of frayed string. “Ah well, if you’ll just sign here, we’ll get them out of the truck so, eh?”

The babydoll sheep were the last piece of Emily’s intricate jigsaw. Once we’d finally done the deal and bought the place from Estelle, her every waking moment had been spent planning and bringing to life the vineyard she had always dreamed of – her own vineyard. It was smaller, perhaps, than in those dreams, but our new-found circumstances meant that it didn’t have to provide much of an income and so she could do whatever she pleased without having to worry about the economics of scale. We were happy enough as long as we didn’t end up having to sell our organs to pay for it. I’d read somewhere that you could make a small fortune making wine, but only if you started with a big one. The vines that had been planted many years before at the back of the house, on the slope that ran down to the river, had long been neglected. Some of them, she kept and nursed back to health. Others, she ripped out, ploughed the land and renourished the soil to start afresh. Then she transplanted some young vines that she bought from a producer she’d met at a wine show in France a few years before and… we waited.

Cara is Missing

Cara is Missing Bad Things Happen

Bad Things Happen